Morocco's Timeless Struggle: From Ancient Granaries to Modern Bread Waqfs

Morocco is initiating an ambitious new phase in disaster readiness through a 7-billion-dirham project aimed at establishing vital stockpiles throughout the country. However, this endeavor goes beyond contemporary strategies; it draws heavily upon a legacy of inventive resilience measures, including traditional granary techniques and venerable organizations that have historically protected those most at risk. Explore the compelling methods Morocco has used to withstand challenges over many generations.

Morocco is enhancing its preparation for crises and urgent situations With the establishment of critical reserve centers, these platforms were initiated following royal directives. Intended to cover all 12 provinces of the kingdom, they form an integral part of a 7-billion-dirham initiative focused on rescuing, aiding, and caring for impacted communities during natural calamities.

Anticipating devastating events such as the Al Haouz earthquake in September 2023, which claimed numerous lives and displaced countless individuals, this significant undertaking upholds Morocco’s extensive tradition of handling crises.

Over its history, Morocco has encountered numerous natural calamities such as flooding, droughts, food shortages, and disease outbreaks. On each occasion, Moroccans have devised methods to manage these challenges, often employing specialized organizations, building infrastructures, engaging religious groups, or showing acts of kindness.

This article delves into how Diwida examines Morocco’s historical approach to unforeseen occurrences and its methods for managing crises.

Storing fortresses, Igoudar

For generations, Moroccans have recognized the importance of food security when facing difficult periods, making food storage a crucial aspect of their heritage. The igoudar, which refers to multiple agadirs, represent communal storages typically constructed by tribes in the Anti-Atlas and High Atlas areas as preparation for potential shortages.

Regarded as one of the earliest versions of banking institutions, these secure storage buildings were deliberately placed on high ground and built with robust materials like thick stone or compacted earth. They look much like forts or miniature castles from afar, complete with watchtowers, restricted entry points, and sophisticated lock mechanisms. Within their confines, you'll find levels divided into smaller rooms serving as vaults for items such as grain reserves, precious jewels, and significant paperwork referred to regionally as Arraten.

French ethnographer Jacques Meunier In his examination of Igoudar, he points out that Igoudar aided in addressing "the inadequate production to fulfill basic needs and the unpredictability of crop yields—in the Souss area, for instance, just one out of every four or five harvests turns out well." He also notes that "the distance from markets and the challenging transport conditions render swift and consistent restocking unfeasible," underscoring the geographical hurdles faced by the region.

A remarkable feature of Igoudar is their sophisticated storage system, especially designed for long-term conservation, which was vital during periods of poor harvests and food shortages. This system utilized active ventilation to stop the grain from becoming too warm, with certain Igoudar structures reportedly capable of maintaining stored grain for 25 to 30 years.

A further responsibility of the Igoudar was to maintain unity during challenging times. Storing grain in the Igoudar vaults entailed obligatory contributions , which were subsequently redistributed following the harvest to guarantee that every tribal member had enough food, showcasing unity and resourcefulness during periods of significant hardship.

Wealthy, powerful zawiyas

Yet, what occurs when crises linger and hunger sets in, eroding the stored provisions? Throughout Morocco’s past, immigration resulting from calamities, illnesses, or starvation has been observed as people searched for safety in other areas or among less afflicted clans. Others found solace within zawiyas, which were prominent Sufi mausoleums gaining significance in Morocco around the 15th century before spreading throughout the nation.

These influential organizations, typically backed by contributions (which include gifts or hadiyas, tributes or zyaras, and endowments or hibas), offered security, not just against the Makhzen but also from famine and various difficulties. As Moroccan ethnographer Mohamed Maarouf notes, A Multi-Disciplinary Exploration of Moroccan Magical Traditions and Customs That zawiyas "provided refuge to vulnerable farmers burdened by the excessive taxes imposed by the Makhzen... individuals incapable of labor turned to the guardianship of saints, relinquishing their lands to the shurfa in exchange for sustenance, sanctuary, and lifelong security." Additionally, Maarouf notes that these zawiyas extended charitable assistance to the destitute, travelers, domestic staff, and enslaved people.

Maarouf asserts that the zawiyas wielded significant influence from the reign of the Marinid dynasty in the 13th century through to the era of the Alawite dynasty in the 17th century, particularly when facing hardships like famines and diseases.

Lending, philanthropy, and alternative options

During periods of scarcity, drought, and famine, Moroccan Sultans would lend money to tribes to help them rejuvenate their crops. This practice is discussed in a book about the historical events in Morocco. Famine and Epidemics in Morocco During the 18th and 19th Centuries Moroccan historian Mohamed Amine el Bezzaz details how the sultan assisted the Beni Ahsan tribe close to Rabat during the challenging farming period between 1780 and 1781. He notes, "Owing to the starvation that impacted local cultivators, large tracts of farmland were left uncultivated. Recovery efforts in certain parts of the Gharb area could be achieved solely due to support provided by the Makhzen; specifically, the Sultan lent a substantial amount to the Beni Ahsan clan for them to farm portions of their territory."

When the sultan or Makhzen failed to offer loans, those in dire straits found assistance through waqfs. El Bezzaz remarks, "The individuals who managed to accumulate and store supplies were naturally the affluent ones. In contrast, the impoverished had little to set aside. Nonetheless, they received support from charitable deeds and communal generosity."

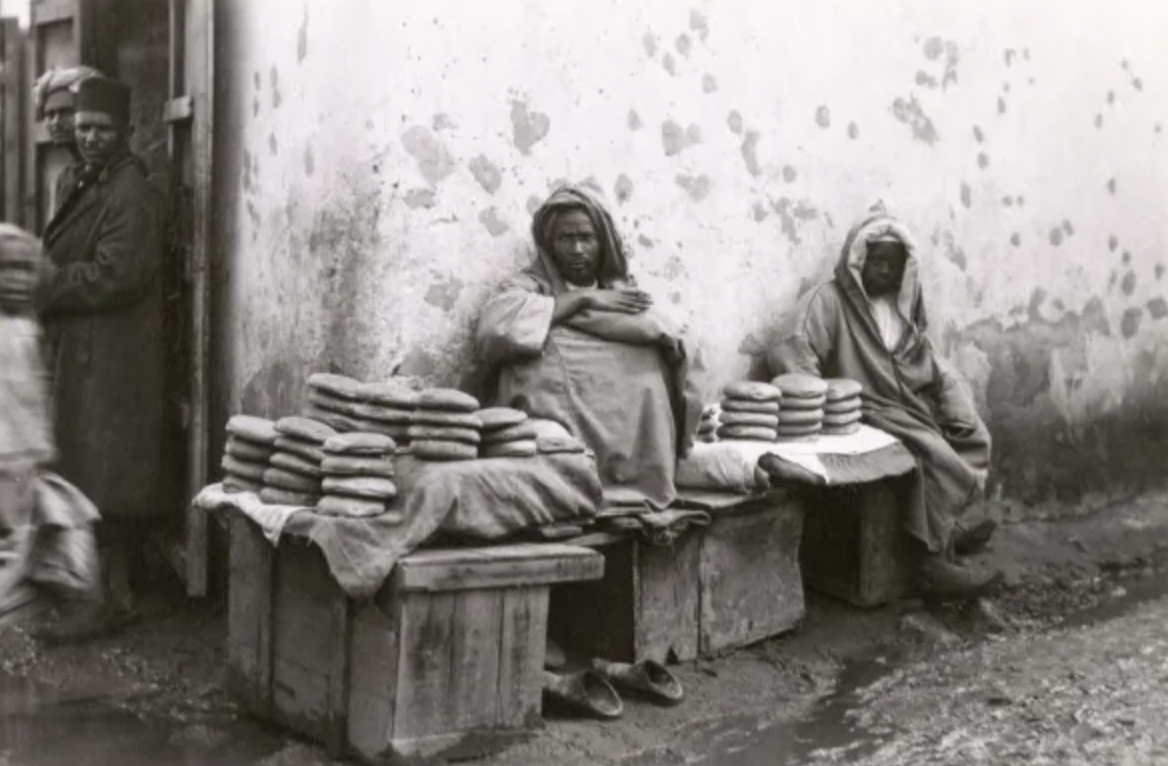

No Moroccan city lacked households that set aside part of their land for social assistance, referred to as awqaf (endowments). These endowments were particularly designated, for instance, for the regular distribution of bread—a form of charitable giving prevalent across the region.

Legal documents and notarial records from Tetouan, which date as far back as the 18th century, document these philanthropic endeavors. Among them was an instance wherein a woman in Tetouan left one-third of her assets to finance the acquisition of bread for distribution among those less fortunate. Consequently, this practice lent the term "bread waqf" significant recognition.

Additional effective approaches to address food and water scarcity involved infrastructures developed jointly by the Makhzen and local communities. These included underground storage units known as matmora, which preserved grains in subterranean cavities, along with reservoirs such as the Sahrij. built by Moulay Ismail in Meknes, together with adjacent storage facilities, previously misidentified as his stables, to house grains.